- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- An immense and catastrophic explosion of a nearby supernova still graces our sky

An immense and catastrophic explosion of a nearby supernova still graces our sky

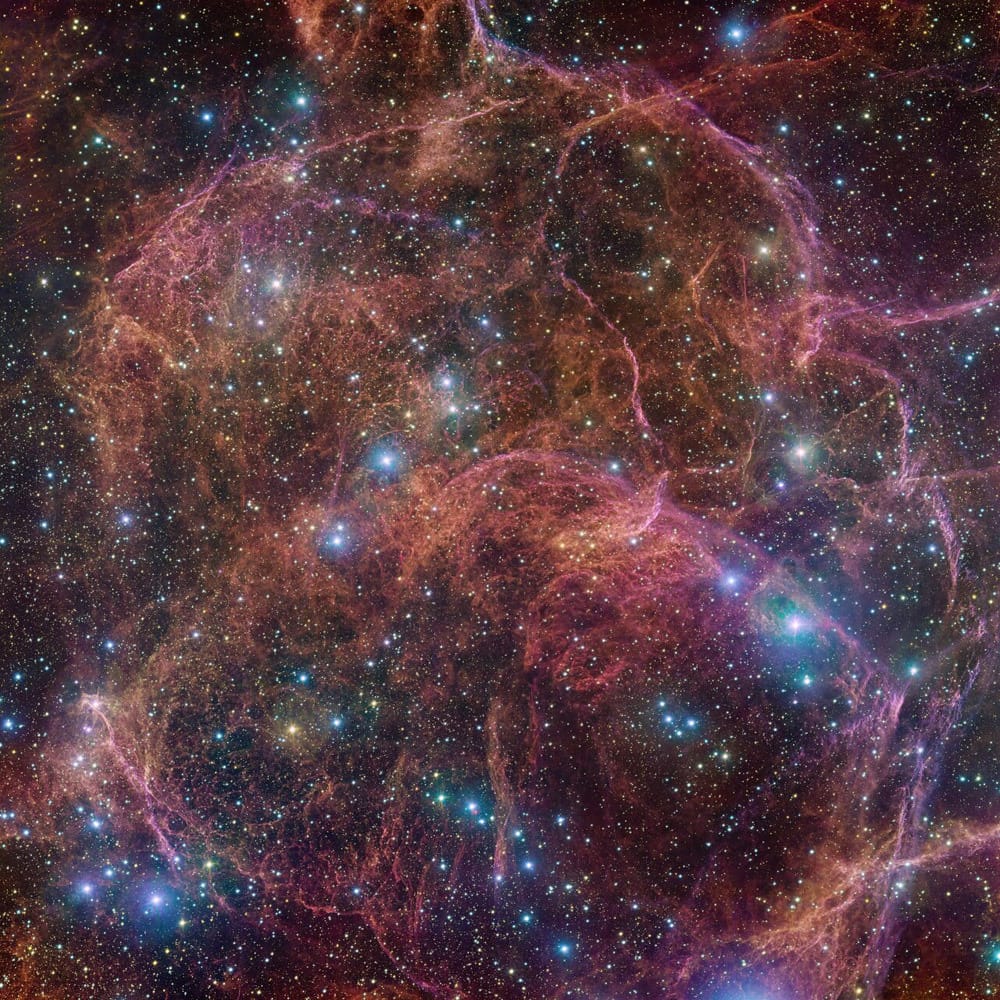

The Vela Supernova Remnant is a masterpiece of chaos

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

January 1, 2026 Issue #979

[Since this is a special issue that falls on New Year’s Day, I’ve made it public so everyone can read it. I’ve also opened commenting to everyone as well, so read to the end and feel free to leave a note!]

The beauty and chaos of an exploding star

The Vela supernova remnant is terrifying and gorgeous

Sometimes, stars explode.

This happens at the ends of their lives — I mean, duh, since when a star explodes it’s done either way. But in this case I mean when one runs out of fuel in its core to fuse into heavier elements, which is what generates the vast energy needed to heat the interior of the star and keep it from collapsing under its own weight. Not all stars end this way — the star needs enough mass to generate the immense internal pressure needed to fuse lighter elements to heavier ones all the way up to iron. This story is quite complicated, but in a nutshell iron takes more energy to fuse than it generates, plus as it fuses it eats up the electrons around it, and those too help support the core of the star against its internal gravity.

When iron fusion starts, the star is doomed. The core collapses, and as it does it generates so much energy so rapidly it positively dwarfs its earlier output, which was already pretty terrifyingly fierce. The blast of energy screams through the upper layers of the star, giving them so much energy they are torn away from the star: an explosion. Technically, a supernova. The resulting fireball is so intense it can outshine a galaxy, and be seen for billions of light-years.

Obviously, you don’t want one of these to be too close. But it does happen — rarely, but the timeline of Earth is long. And, in fact, only 11,000 or so years ago just such a star blew its top when it was just a little over 900 light-years from Earth. That’s close, and the resulting explosion would have been easily visible in daytime. It likely didn’t do any actual damage to our planet — we’re here, after all, so Earth wasn’t vaporized or anything — but still it would’ve been a sight.

Now, all these millennia later, what we see in that spot is the magnificent Vela Supernova Remnant, the debris still expanding away from the site of the blast.

And did I say “magnificent”? Yes. Yes I did:

The Vela Supernova Remnant. Yowza. MInd you, I had to shrink this a lot to fit here as well as make the filesize reasonable. Credit: ESO/VPHAS+ team. Acknowledgement: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit

This incredible image was taken by the confusingly named Very Large Telescope Survey Telescope (or VST) — a 2.5-meter wide-field telescope that’s located right next to the much more massive Very Large Telescope (or VLT). VST has a much larger field of view than the VLT, and part of its mission is to image large areas of the sky that VLT will then see in detail. VST can see a section of the sky one degree across (about 4-5 times the area of the full Moon) and has the whopping huge 256 megapixel OmegaCAM to observe it. It’s a powerful combo.

This image of the Vela remnant is a mosaic of several images that ended up with 554 million pixels (you can get the full resolution TIF here). The images used five different filters to select light from the ultraviolet, infrared, and visible light (including what’s called H-alpha, light emitted specifically by hydrogen gas which is shown in red in the image).

Here’s the part that kills me though: this vast image only shows a part of the Vela remnant! The expanding gas is about 130 light-years across, so from Earth we see it as about 8° across, far larger than even VST’s field of view. It would take over 60 observations just to cover the whole structure in one filter. So we’re only seeing a piece of it here.

This is a small (!) section of the full-resolution image, still so big I had to shrink it from 5,000 to 1,000 pixels to get it to fit here. Click it to get access to the full 23,000 x 23,000 pixel image. ESO/VPHAS+ team. Acknowledgement: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit

After all these centuries the expanding gas from the exploded star has been plowing into the much thinner gas between the stars (what we call the interstellar medium), sweeping it up and compressing it like a snowplow through snow. This is what creates the thin filaments and web-like structure to the remnant. While what we see here is mostly hydrogen, there is also a lot of other stuff too, including elements like oxygen, nitrogen, iron, and more. When the Universe was young, such heavier elements didn’t exist; it was only through explosions like this one that these elements (some made inside the star while it was still “alive”, some created in the searing forge of the supernova event) were created and scattered into space. The high-speed ejected debris hits other gas clouds that collapsed to form stars, and the process repeated. Eventually one of these gas clouds formed the Sun, and Earth with all those elements in abundance.

What does this mean to you? Literally everything. The iron in your blood, the calcium in your bones, the oxygen you breathe, the nitrogen in our atmosphere, all and more were alchemically produced in such explosions. You owe your existence to supernovae!

How’s that thought for the beginning of a new year?

When I was in high school, I think it was, I bought a poster of the Vela remnant that hung on my wall for years. I used to stare at it, thinking of what must have happened to create such a chaotic and yet somehow ordered mess. I was fascinated by the two parallel arcs seen here too, one in the lower half of the image and the other near the top. I understand now how the gas was compressed as the explosion expanded in a near-sphere, so of course you get nested filaments like that, but back then I was still years away from learning how all this worked. But the photo was mesmerizing, and was no small part of what kept me inspired to become an astronomer.

So, as 2026 takes the handoff from 2025, I show you this incredible image that is a metaphor for beginnings and endings and new beginnings, and a symbol of my own journey to explore and understand the Universe. What inspires you? I hope you find it in the coming year, and it helps you along down your own path.

Et alia

You can email me at [email protected] (though replies can take a while), and all my social media outlets are gathered together at about.me. Also, if you don’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter! And feel free to tell a friend or nine, too. Thanks!

Reply