- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- Asteroids from Venus pose an invisible — but uncertain — threat

Asteroids from Venus pose an invisible — but uncertain — threat

Bottom line: we need to look for them

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

October 6, 2025 Issue #940

The threat from Venus

Asteroids that share the orbit of our sister world could be a danger to us

Most of the asteroids in the solar system are in the main belt, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Billions of them orbit in that vast region of space. However, not all of them do: mostly due to the gravity of Jupiter, some can be tugged gravitationally, changing their orbits and dropping them down closer to Earth. Any space rock bigger than 140 meters across that gets within 7.5 million kilometers of Earth is considered to be a Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (or PHA)—one that can eventually hit us. There are very roughly 2,000 such rocks on that list (depending on which list you look at).

That’s a lot, though none poses an immediate threat to us. But those are only the ones we’ve detected; we don’t know of a lot of them, and those are a cause of concern.

One particular problem is the group of asteroids that orbit closer to the Sun than Earth does. From our point of view, they rarely get far enough from the Sun in the sky to observe; they’re up during the day or at best at twilight. Quite a few such asteroids are known, but they’re hard to spot.

A team of astronomers has identified one such group of worrisome rocks: ones that share an orbit with Venus. They’ve found that these can pose a threat to Earth [link to journal paper].

Venus orbits the Sun at a distance of about 108 million km, while Earth is 150 million km out. That’s decently close, and in fact it’s the planet in the solar system that can get closest to us. At present, there are 20 known asteroids that are in a 1:1 resonance with Venus, meaning they also orbit the Sun in the same amount of time Venus does. They’re not on the exact same orbit as our sister planet; they have elliptical orbits that take them farther in and out from the Sun than Venus, but this averages out to them having the same orbital period.

All of these rocks have a high eccentricity, meaning their orbits are quite elliptical. That is most likely a selection bias: we can only see them if they can get close enough to Earth to be bright enough to spot, and also get far enough from the Sun to see them as well. If they orbited in a circular path with Venus they’d never get bright enough to see. It stands to reason that there is a population of such asteroids on these more circular orbits that we cannot see.

What the astronomers did is simulate the orbits of these asteroids over time. The gravity of the other planets subtly affects them, changing their orbits from one shape to another. They find that it takes roughly 12,000 years from them to move from one kind of co-orbital configuration to another — there are various ways an asteroid can share an orbit with a planet like Venus, some quite complicated. But it’s possible they can move into much more elliptical orbits that takes them much closer to Earth, in fact close enough to impact us.

Can we spot such asteroids? Yes, but not easily, and not all of them. There is a program with the newly commissioned Vera Rubin Observatory to observe the sky low to the horizon at twilight to look for asteroids closer to the Sun; however it’ll be a while before we see those results. A better place to look for them is from Venus, or at least with a space-based observatory closer to the Sun than Earth is, so it can see those asteroids by looking outward, away from the Sun rather than toward as we have to from our planet. NASA is building such a mission: the Near-Earth Object Surveyor, which will orbit the Sun in a stable gravitational point (called the L1 point) about 1.5 million kilometers closer to the Sun than we are. It should be able to spot a lot of asteroids difficult to see from Earth. But that’s still too close to us to spot all of them.

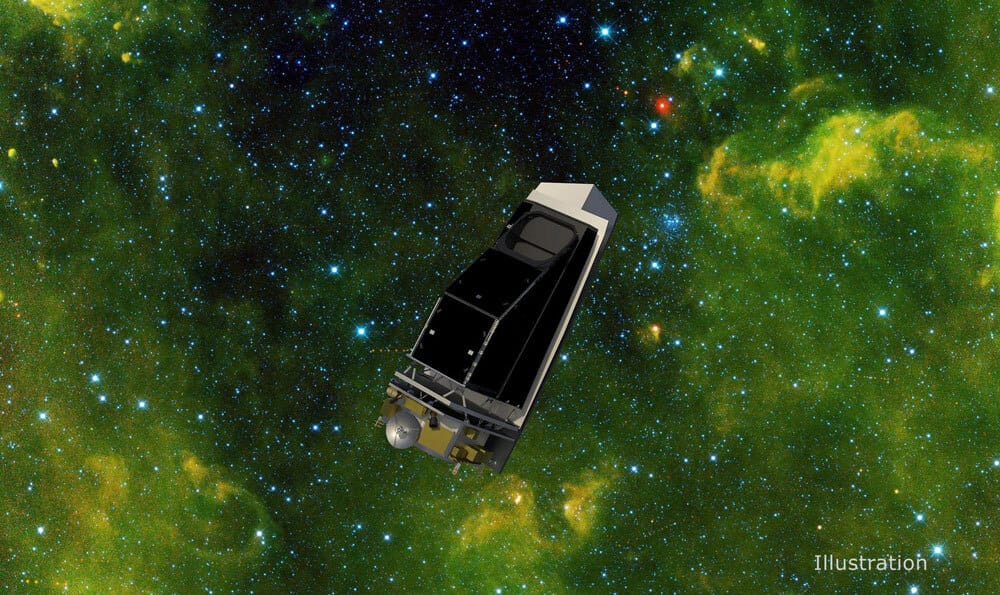

Artwork of NEO Surveyor against an actual image taken by NASA’s WISE infrared observatory. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

Better yet would be an observatory at the Sun-Venus L2 point, about a million kilometers farther out from the Sun than Venus. This would be perfect for scanning the skies to see almost any asteroid near Venus that could also threaten Earth. Unfortunately, no such mission is planned for now.

These Venus co-orbiters are a threat for sure, though how big of a threat is unclear. We don’t know how many there are! One thing that makes me breathe a little easier is that we haven’t had a big impact on Earth from any kind of asteroid for over a century, and they’re likely hundreds of years apart on average.

That’s good! But it also means we can’t wait forever to look for them while they’re still a safe distance away. The more eyes we have on the sky — and the more places we have them — the better.

Et alia

You can email me at [email protected] (though replies can take a while), and all my social media outlets are gathered together at about.me. Also, if you don’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter! And feel free to tell a friend or nine, too. Thanks!

Reply