- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- Europa’s ice is pretty thick

Europa’s ice is pretty thick

Also: a barred spiral galaxy more distant than expected

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

January 29, 2026 Issue #991

How thick is Europa’s ice?

Juno observations show the ice shell covering Jupiter’s moon may be 30 km deep

Europa, as seen by the Juno spacecraft on September 29, 2022. This image was processed by the amazing Kevin Gill, a software engineer who does amazing work putting together planetary images from spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill

Europa is a moon of Jupiter, about the same size as our Moon. It’s very icy, and we’ve known for some time now that under that icy surface is an ocean of liquid water of unknown depth, though probably some tens of kilometers deep. At the bottom is likely a rocky mantle over a metallic core.

Out at Jupiter’s orbit there’s only 4% as much sunlight as on Earth, so it’s cold. The surface of Europa is a chilly -160°C (-260°F), so the ice is almost as hard as granite is on Earth. The ocean underneath is heated by tides, Jupiter’s mighty gravity stretching and squeezing the moon as it orbits, creating friction that warms the interior. Water plus minerals from the seabed plus energy from the tidal heating means there’s a possibility for life in that ocean. We don’t know, because the thick ice shell blocks us from seeing it.

How thick? It’s been estimated to be from maybe 3 km to over 30 kilometers deep, but it’s hard to actually measure. However, new results published last year may provide the answer [link to journal paper].

Juno is a spacecraft that orbits Jupiter in a wide ellipse, dropping down to just a few thousand kilometers over the huge planet’s north pole, then swinging out to 8 million km, well past the four big moons. It usually doesn’t get close to them — Juno was designed to look at Jupiter, not its moons — but the mission planners put together a series of trajectories that took Juno past some of the moons. On September 29, 2022, it flew just 360 km over Europa’s surface, taking some amazing images and a lot of data of the icy world underneath.

Any object warmer than absolute zero emits light, and at Europa’s temperature that will be in the radio wavelength range (reminder: radio waves are light, just with longer wavelengths than you’re used to), and Juno has instruments (called radiometers) that can measure those radio waves with a wavelength range from about 11 to 50 centimeters. The brightness of the light is a proxy for temperature. Using that data to plug into a physical model of how heat moves from the warmer ocean upwards into the ice, the scientists could estimate the ice depth.

The result: in the areas Juno flew over, the ice shell is about 30 ± 10 km thick.

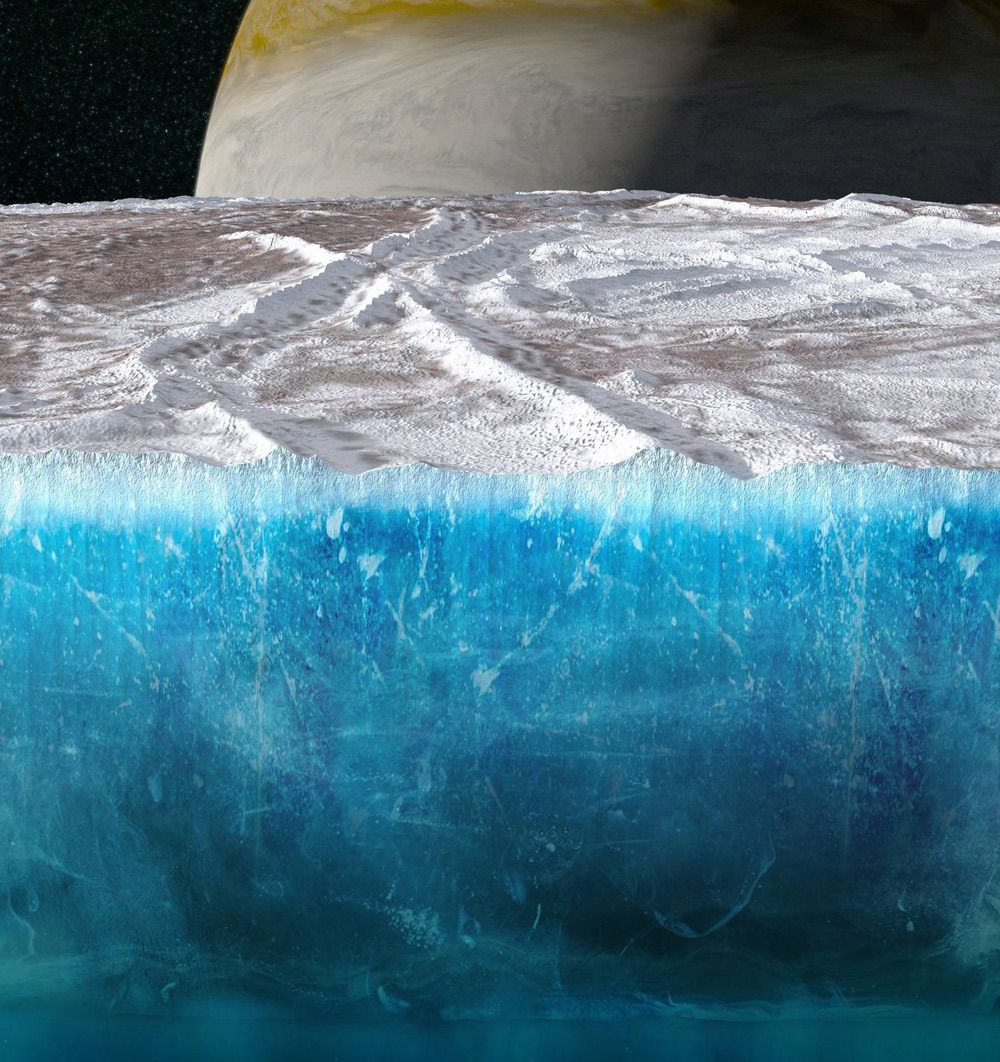

Artwork depicting a cutaway of Europa’s surface, showing the thick ice shell above an ocean, with Jupiter filling the sky. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Ouch. That’s more than I would’ve hoped. That makes designing a lander to melt a probe into the ice and down into the ocean pretty hard. A mission like that likely wouldn’t get built for a decade or two anyway, but still. That’s a tough design goal.

It’s possible the ice is a bit thinner; the presence of salt in the ice means it transmits the heat a little bit less efficiently, so if there’s salt in the Europan ice the shell could be thinner by maybe 5 km. Note that’s less than the uncertainty in their measurement, so it’s impossible to say from these data alone what’s in the ice.

It’s also been theorized that cracks in the surface could help transport material like oxygen down into the ocean, but the Juno data don’t show any. There are “scatterers” in the ice; irregularities like cracks and pores, but they’re small, only a few centimeters wide, and not enough to get anything from the surface down into the water so far below.

What does this mean for life under Europa’s surface? Not much, directly, but this does tell us more about the structure of the moon, which can be used to put into models for how the interior behaves. It also shows that we have a long way to go — literally — if we want to see any potential alien fishies swimming there.

Subscribe to Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

Already a paying subscriber? Sign In.

A subscription gets you:

- • Three (3!) issues per week, not just one

- • Full access to the BAN archives

- • Leave comment on articles (ask questions, talk to other subscribers, etc.)

Reply