- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- NGC 3370: Stepladder to the Universe

NGC 3370: Stepladder to the Universe

Also, it’s a very pretty spiral galaxy

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

November 10, 2025 Issue #955

A galaxy among galaxies

Hubble image of NGC 3370 gets better the more you look at it

I have a gift for you! I hope you like deep Hubble Space Telescope images of a gorgeous galaxy with a ton of very interesting and beautiful things to look at and ponder.

And if you don’t, why the heck are you subscribing to this newsletter?

NGC 3370. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Riess, K. Noll

Wow! That’s NGC 3370, a spectacular spiral about 95 million light-years from Earth. This image combines observations taken over two decades, using the Advanced Camera for Surveys and the Wide-Field Camera 3, two workhouse instruments on Hubble. It combines images from the blue, green, red, and near-infrared parts of the spectrum, too, yielding fantastic colors and depth. As usual I had to shrink it to make it fit the newsletter; click here for much higher resolution shots (including the full-res 4,200 x 3,400 pixel version).

These observations were made as part of a couple of different projects to determine the distance to this galaxy. That’s important because those measurements can then be used to get the distances to even more distant galaxies, which are otherwise difficult to determine accurately.

The key here is that NGC 3370 is the host to a special kind of star called a Cepheid variable, and a special kind of exploding star called a Type Ia supernova. Cepheid (pronounced SEFF-ee-id) variables are stars that expand and contract in physical size over the course of a few days or weeks. The internal process is a bit complicated, but the end result is that they get brighter and dimmer over time. The brilliant astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt figured out that the change in brightness is correlated with how long it takes for the brightness to change; the longer the time the more luminous the star got. Eventually, the distance to nearby Cepheids were directly measured via parallax, which was a huge deal: by using those nearby stars as calibrators, we could then measure the distance to Cepheids much farther away — if you know how much energy a star emits, and how bright it appears in the sky, you can calculate its distance. Since we see Cepheids in other galaxies, this gave us a way to figure out how far away those galaxies are!

A century ago, Edwin Hubble’s team used this to get the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy, finally proving beyond doubt those “spiral nebulae” in the sky were actually galaxies in their own right, and not gas clouds in the Milky Way.

But Cepheids can only be seen out to a certain distance (about 90 or so million light-years). So how do we get the distances to galaxies that are farther than that?

Ah, now we’re back to those Type Ia supernovae. These all explode (more or less) with the same energy, so if we can measure the distance to a few nearby ones, we can use that to figure out how far away more distant ones are. The Hubble Cepheid observations nail the distance to NGC 3370, and that galaxy also hosted a Type Ia supernova called SN 1994ae. That means we got the distance to that supernova, and it can be used (together with dozens of others innearby galaxies) to calibrate the distance to other, farther away galaxies that hosted the same kind of supernova. This idea is called the cosmic distance ladder.

It’s actually difficult and painstaking work, and a lot of Cepheids and supernovae are needed for it to work. Those nearby ones are critical, which is why NGC 3370 is one of many galaxies observed with Hubble to measure their brightness (I’ll note that the telescope was named after Hubble in part because of his Cepheid observations, and getting more distant Cepheid observations is a key program for the telescope).

OK, so that’s NGC 3370. But there’s more stuff in the image, too. My favorite bit is to the left of the galaxy:

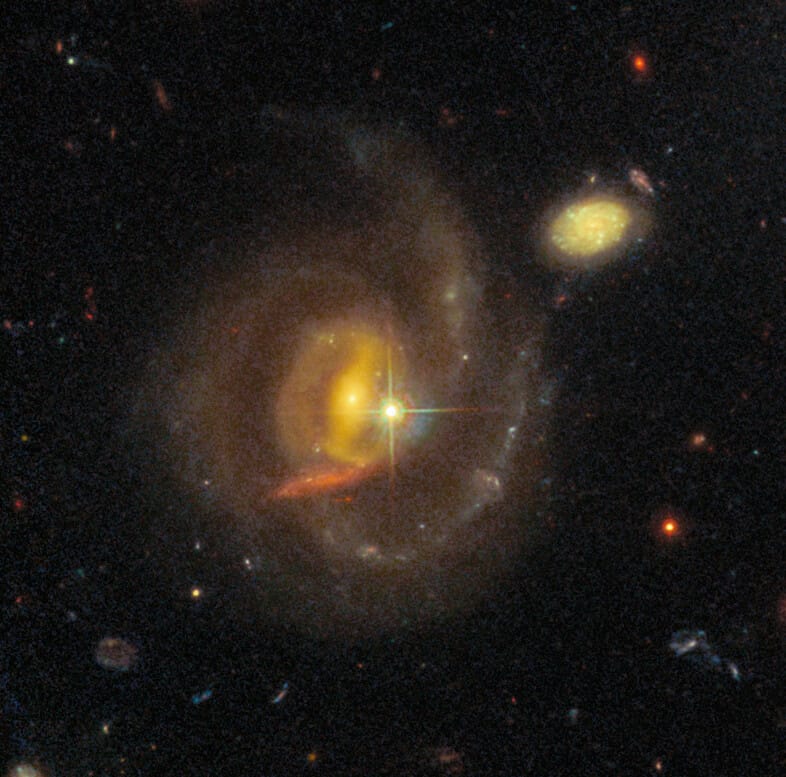

Wheels within wheels. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Riess, K. Noll

I looked in a database of astronomical objects and didn’t find a name or catalog entry for this galaxy. But it’s clearly a spiral galaxy (a barred spiral, for that matter) and it’s presumably much more distant than NGC 3370. Without knowing its true size that’s not easy to guess.

I love this part of the image because of its layers. That bright star in the center is very likely inside our own Milky Way galaxy, so maybe a few thousand light-years away (more or less). But the spiral galaxy is hundreds of millions of light-years away! Not only that, but that red smudge just below the center of the galaxy is an even more distant galaxy, reddened both due to the expansion of the Universe as well as dust in the foreground galaxy — made of tiny grains of rock and soot created by dying stars, dust absorbs and scatters blue light but lets red through, so it reddens objects behind it, similar to how junk in our air makes the setting Sun look red.

There’s also that compact spiral to the upper right. Is it closer? Farther? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

There are a lot of other, even more distant galaxies scattered around the image. The smallest and faintest might be billions of light-years away. For many, when the light we see left them, Earth didn’t exist. The atoms of our planet were still scattered around in a nebula somewhere, or still being cooked from lighter elements inside a massive star destined to someday explode and seed those atoms into the nebula.

So yeah. Take a good, long look at this image. There’s a lot to see in it…like all of space and time.

Et alia

You can email me at [email protected] (though replies can take a while), and all my social media outlets are gathered together at about.me. Also, if you don’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter! And feel free to tell a friend or nine, too. Thanks!

Reply