- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- The irony of Supernova 1885A

The irony of Supernova 1885A

It proved the Universe was bigger than astronomers thought, but they couldn’t believe it

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

November 17, 2025 Issue #958

Nova or supernova? A time when astronomers got it exactly wrong.

An extragalactic supernova was used as evidence the Milky Way was the whole Universe

Back in BAN #845 from February 2025, I wrote a note about how, in modern times, there have only been two supernovae ever seen in other galaxies that got bright enough to be seen by the naked eye: Supernova 1987A and Supernova 1885A, and, by coincidence, I’ve done research on both of them! Go ahead and read that — it’ll only take a minute — and then come on back.

<Jeopardy music plays>

OK, done? Cool.

Some years ago I was reading about the history of galactic astronomy, and how we figured out that other galaxies existed. It’s a pretty interesting story, and an excellent lesson in how science works. The basic idea is that for a long time, astronomers thought the Milky Way was the entire Universe, and everything we saw in the sky was inside it. The observations of the time supported this idea, and there was little evidence to the contrary.

But there was some, and there were astronomers who were willing to disagree with the consensus. The crux of the issue was the existence of what were called spiral nebulae: fuzzy objects that looked like gas clouds commonly seen all over the sky (like the Orion Nebula), except they had a distinct spiral structure to them, like a pinwheel. Most astronomers thought they were small objects inside the Milky Way, but others suspected they were galaxies in their own right, and the Milky Way was just another example of them that we happened to be inside of.

This led to what’s called The Great Debate — two astronomers literally debated whether the Milky Way was everything there is, or just one small part of it. This debate occurred in 1920, and you can read all about it on Wikipedia or Astronomy magazine. APOD also has a more detailed write-up by the astronomer/historian Virginia Trimble.

One item in the debate was the “nova” seen in the Andromeda Nebula (what we now call [SPOILER ALERT] the Andromeda Galaxy) in 1885. The term nova comes from the Latin nova stella, or “new star”; it’s when a new star suddenly appears the sky when none was seen there before. They had been observed for centuries, but no one in the 1880s (or the 1920s, for that matter), knew what caused them. We now know it’s when a white dwarf draws material off a companion star, which piles up on the surface until it gets squeezed so hard by the dwarf’s immense gravity that the matter explodes, creating a very bright flash that lasts for days or weeks; hence the appearance of a new star in the sky. But in 1920 this wasn’t understood yet.

At the time, several had been detected in the Andromeda Nebula, which was odd. If the Milky Way were the entire Universe, why were so many novae appearing in Andromeda? And why were they all faint? That seemed to support the idea that the nebulae were in fact galaxies.

But then the one in 1885 went off, and was far brighter than the other novae. In fact — and here’s the fun bit — they argued that if Andromeda were actually outside the Milky Way and millions of light-years away, the explosion would have to be ridiculously powerful, so energetic that the idea could be dismissed out of hand.

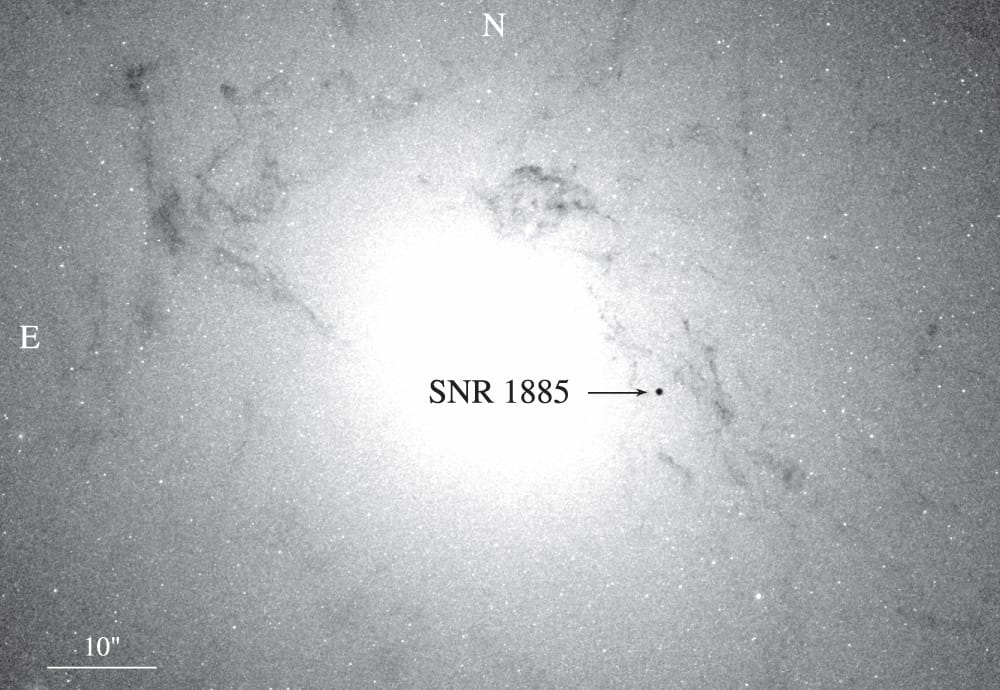

The expanding debris from SN 1885 absorbs light from the galaxy behind it, so this Hubble image of the Andromeda Galaxy core shows it as a black spot. Credit: Fesen et al. 2015

Mind you, at the time they didn’t understand the difference between a nova and a supernova! Supernovae had been seen in our own galaxy, but were assumed to be novae that happened to be closer to us, and therefore appeared brighter — the term supernova wasn’t even coined until more than a decade after the Debate. The mechanism behind a supernova wasn’t known, so it wasn’t understood how truly luminous they could get, so it made sense to assume they were just another flavor of nova.

We now know that a supernova is when a star catastrophically explodes; it can be a high-mass star at the end of its life (a core-collapse supernova) or a feeding white dwarf, like in a nova, but so much matter piles up on its surface that the resulting explosion completely destroys the dwarf star (1885A was the latter). In either case the energy released can be several billion times the Sun’s brightness! A normal nova peaks around 100,000 times the Sun; huge, but nowhere near a supernova.

This is what makes me smile at the irony. Astronomers argued the 1885 nova — which actually was a supernova — showed that the Andromeda Nebula must be close to us, but in fact proved the opposite. They just didn’t know the difference between the two events.

It didn’t take long for the debate to be over. Just three years later Edwin Hubble and his team of astronomers showed conclusively that Andromeda was in fact much farther away than previously thought, and was therefore a galaxy in its own right. This also showed that the 1885 event was in fact Supernova 1885A (the “A” is a formality, showing it was the first supernova seen in that year, but it was also the only one), and had they understood that the Debate would have been much shorter.

And then, of course, just 102 years later, I’d wind up doing some research on it that led to my first co-authored published paper. It tickles me to have worked on that particular event — I do love a good irony — and then to go on to work on Supernova 1987A, which revolutionized astronomy in a very different way.

Science works this way pretty often. We gather evidence, make observations, and try to fit them into some pre-existing paradigm. But sometimes the data don’t fit, and as more piles up it can result in a revolution (an explosion, if you will) that changes how we see the Universe. Suddenly all those mismatched puzzle pieces fit together much better.

…until we start seeing fraying around the edges of that idea, and have to rethink it again. As time goes on the restructuring tends to get smaller because we get closer to the truth, but there’s still plenty of room for big revolutions, too. We just have to make sure that when they come along we recognize them (and, conversely, don’t think we’re seeing a revolution when one isn’t there).

Et alia

You can email me at [email protected] (though replies can take a while), and all my social media outlets are gathered together at about.me. Also, if you don’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter! And feel free to tell a friend or nine, too. Thanks!

Reply