- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- Watch the Geminids! And a cluster’s stars swirl down the drain.

Watch the Geminids! And a cluster’s stars swirl down the drain.

A great meteor shower for the weekend, and a gorgeous star cluster slowly spins

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

December 11, 2025 Issue #970

Just a note to free subscribers: Normally this would be an issue just for paid subscribers but I’m putting a lot of it “above the fold” so you can see it; I want as many people to know about the meteor shower as possible! Also, remember I’m still having a 20% sale on the premium rate so it’s $4.80 for a month or $48 for a year. Sign up here!

Catch the Geminids this weekend!

It’s one of the best meteor showers of the year

I do so love a good meteor shower, and the annual Geminids is one of the very best. It tends to get short shrift a bit because it happens when it’s so cold, but it’s worth bundling up to get a look.

I won’t belabor what a meteor shower is and how to observe them; I’ve written about them approximately eleventy bazillion times (like here and here). Sky and Telescope has a guide to watching them this year as well. The shower peaks on Saturday night/Sunday morning (Dec. 13/14) after midnight, though if you go out earlier (say around 10:00 p.m. local time) you’ll still see plenty if the sky is clear. The Moon is a waning crescent and doesn’t rise until just before sunrise, so it won’t interfere with the shower at all.

Something I didn’t know is that the shower appears to be getting stronger over time; my friend and colleague Ethan Siegel writes about that for his “Starts with a Bang” column at BigThink. Meteor showers come from debris ejected by comets, and not only does the amount thrown off change over time, our geometry as Earth passes through the debris field (creating the meteors as they burn up high in our atmosphere) can change as well. I’ve noticed the Geminids performing better over the past few years but hadn’t really thought much about it due to the inherent variability of watching a shower; timing is important, as is the Moon and weather. But yeah, this is a good year to go out and see. If it’s clear here I’ll be taking a look myself. It’s always fun to watch the bright flashes of little bits of cosmic ejecta zipping across our sky at high speed.

Gas and stars circle the drain in a spectacular star cluster

NGC 346 shows overall motion, a remnant of how it formed

We think that most stars (including the Sun!) formed in star clusters, dense collections of stars that themselves form from huge clouds of gas and dust called molecular clouds. The clouds are cold, but what little warmth they have is sufficient to keep them inflated despite their gravity.

For a while. If something upsets the balance, like two clouds colliding, their gravity can take over, causing them to collapse in on themselves. As denser knots of material in them grow large, they collapse to form individual stars. Eventually you can get a star cluster that may have thousands of members in it, all gravitationally bound to one another.

This idea predicts that many if not most clusters will have some overall rotation to them, because clouds will typically collide off-center, creating some torque that spins the material up. Many clusters we see don’t have any rotation we can measure, though, while some do. It’s not clear why.

To investigate this idea, a team of scientists used Hubble Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope (or VLT) to look at NGC 346, a huge cluster in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a nearby dwarf galaxy that orbits our own Milky Way. It’s about 200,000 light-years away, which is relatively close as galaxies go, giving them an excellent view of the cluster.

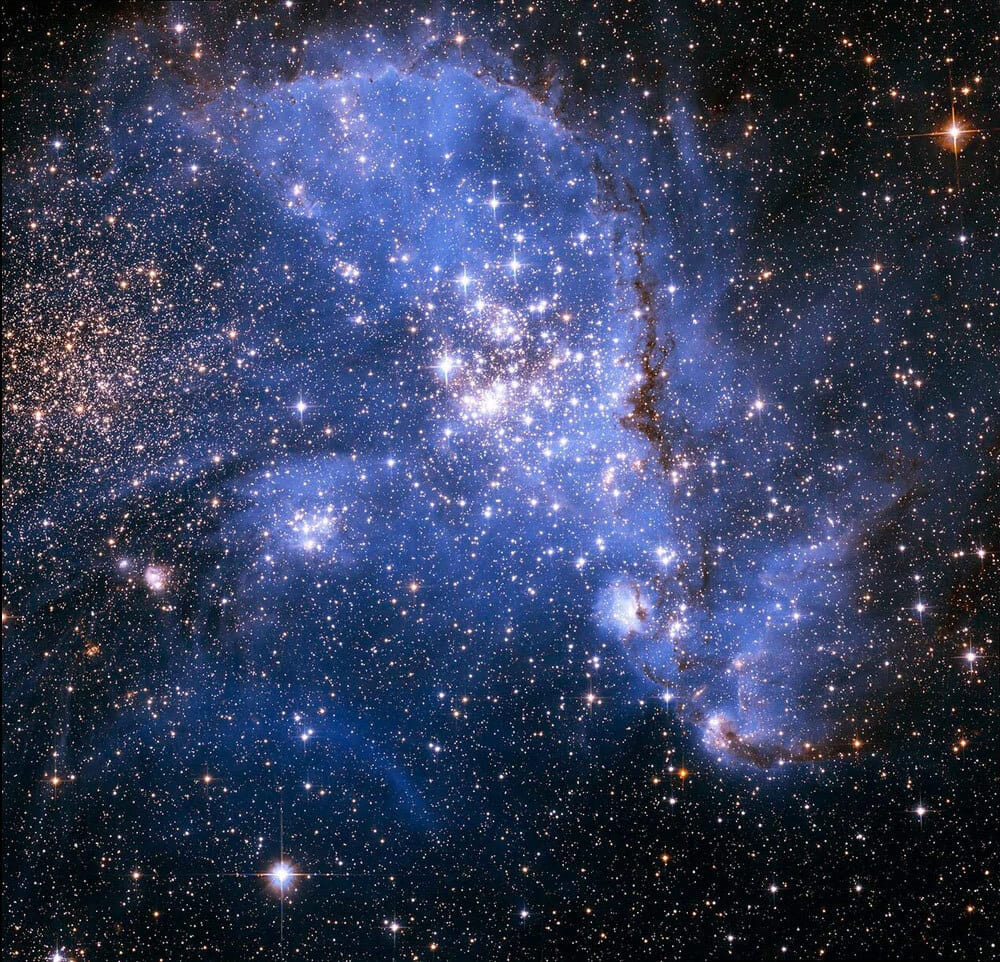

The central part of the cluster NGC 346 as seen by Hubble (what’s shown as blue is actually hydrogen gas), filled with stars. Credit: NASA, ESA, A. James (STScI)

Those stars in the cluster move through space. At that distance the motion is shrunk to near invisibility (like a distant airplane appears to move across the sky slowly despite moving at several hundred kilometers per hour), but over time that motion is still (barely) discernable with Hubble. The longer the time between observations the more the stars move, and the team used images taken 11 years apart out map out that movement.

They also used the VLT to take spectra of those stars and use their Doppler shifts to measure their motion toward or away from us, giving the team a 3D map of their motions. There are several subclumps of stars in the cluster, making things a bit difficult, but they found that one of those clumps shows clear rotation, with the stars taking about 2.5 million years to circle the cluster once. The cluster itself is only about that age, so they’ve likely only made one lap since they formed.

Subscribe to Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

Already a paying subscriber? Sign In.

A subscription gets you:

- • Three (3!) issues per week, not just one

- • Full access to the BAN archives

- • Leave comment on articles (ask questions, talk to other subscribers, etc.)

Reply