- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- A ridiculously jaw-dropping JWST image of a fantastically terrifying star system

A ridiculously jaw-dropping JWST image of a fantastically terrifying star system

Apep consists of three immense and immensely powerful stars blasting out a fierce dusty wind

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

December 1, 2025 Issue #965

The sale ends December 19

A reminder for folks who didn’t check out the previous issue on Friday: I’m having a holiday sale on the price of subscribing to this here newsletter! It’s 20% off, so $4.80 per month or $48 per year. I have all the info you need in the earlier issue.

I’ll mention that it makes a great gift for a geeky friend or family member. No tariffs, no throwing money into a billionaire’s pocket, no supporting iffy companies that support extremely iffy politics. Just me and you. And the entire universe, of course. There’s a lot of cool stuff out there, and I’ll present it to you and them thrice weekly.

JWST eyes Apep, one of the most truly terrifying star systems in the galaxy

Wolf-Rayet stars are just so cool. Also hot. Very, extremely, mind-crushingly hot.

I am fascinated by Wolf-Rayet stars. Perhaps this fascination is like a rabbit staring at a snake (appropriate, as you’ll see), or like when you’re watching a horror movie and can’t look away. In a galaxy of life-ending threats, WR stars sit very near the top of the list.

Why? Well, for one thing, they’re extremey massive stars nearing the ends of their lives. All stars start off fusing hydrogen into helium in their cores, like a controlled nuclear bomb, creating vast amounts of energy that support the huge mass of a star against its own weight. For stars like the Sun that hydrogen supply lasts for billions of years, but the rate of fusion goes up ridiculously rapidly with mass, and stars with 20 or more times the Sun’s heft blow through their entire supply in just a few million years.

Most then start fusing helium into carbon, and when that runs out they start to fuse carbon, and so on. During this process they evolve into a red supergiant (and sometimes a blue one, depending on the exact circumstances). Some blast out so much energy from their cores that the huge envelope of hydrogen making up their outer layers gets blown completely away, torn away by the fierce radiation coming from below.

Wolf-Rayet stars are a subcategory of these stars. We see no hydrogen in them (because their outer layers are gone), just helium and heavier elements, usually loads of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen. And they are bright. It’s not uncommon for a WR star to glow with a million times the energy of the Sun! Such a star would cook the Earth in extremely short order if we replaced the Sun with one.

They also blow out incredible winds of subatomic particles, which form strange and beautiful nebulae around the stars. The wind can also be laden with carbon, which can condense to form dust grains, and in fact WR stars are a major contributor to dust in the galaxy.

And sometimes these winds are bizarre.

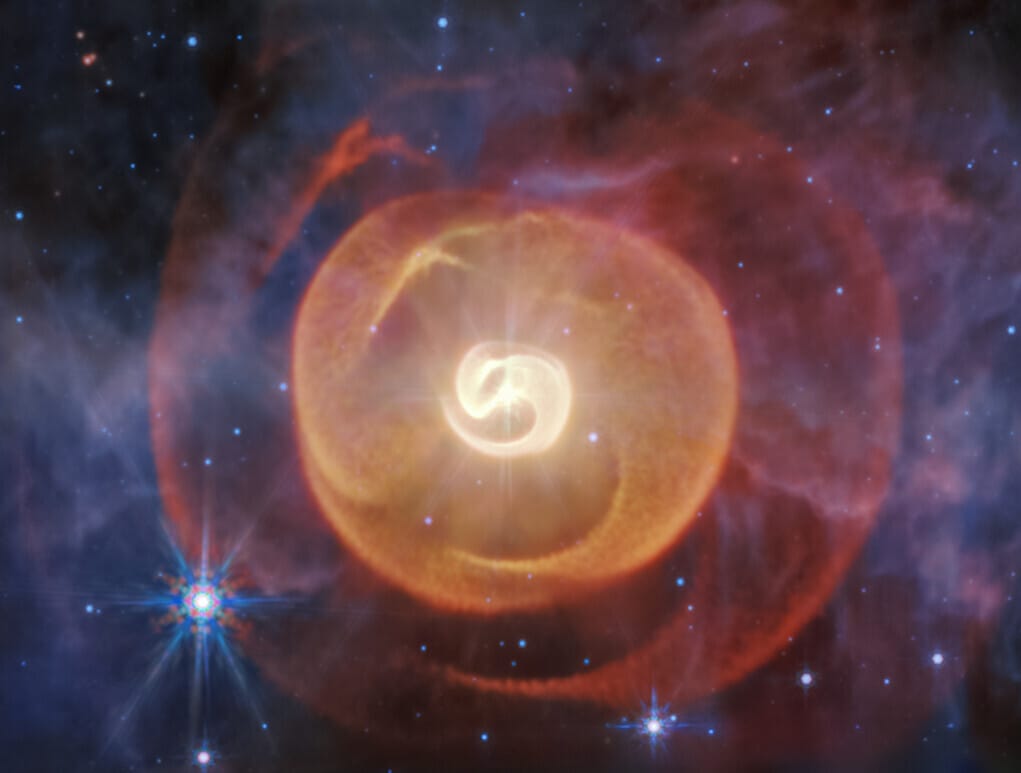

Yeah, no caption will describe this. Just read what I wrote below! Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Y. Han (Caltech), R. White (Macquarie University), A. Pagan (STScI)

Yeah, WHAT?

Apep (named after the Egyptian serpent god of the underworld (hence the rabbit analogy above) and also called Apophis in ancient Greek, for you near-Earth asteroid and Stargate fans) is a trinary system — three stars orbiting each other — and is just so extreme and mind-blowing that it’s difficult to exaggerate.

Two of the stars are Wolf-Rayet stars, both radiating energy at rates hundreds of thousands times of higher than the Sun. These two orbit each other once every 193 years or so. The third star is a normal (ha! “normal”!) supergiant much farther out, about 350 billion kilometers (toughly 50 times Neptune’s distance from the Sun).

So what is going on in that image? It was taken with JWST, which sees light in the infrared part of the spectrum (specifically, at wavelengths of 7.7 microns (shown in blue and green), 15 microns (also green), and 25 microns (red)). The longest wavelength of light you see here is over 30 times longer than the reddest light our eyes can see.

Light in this part of the spectrum is emitted by warm dust, roughly 100 – 300 Kelvin (~ -170 – 30° C). So you’re seeing teeny grains of carbon-loaded dust — basically soot — warmed by the fierce heat of the stars. These observations have been analyzed in two articles recently published (Paper 1, and Paper 2).

The shape is amazing, isn’t it? The two WR stars orbit each other on an elliptical path, and whenever they get close together their winds collide, slamming into each other and blasting away a huge spray of dust. We see this in other WR stars, like WR 140 (which I wrote about for Scientific American, too) and WR 112. This happens once per orbit when they’re closest together, so the pattern repeats. For Apep, that cycle takes nearly two centuries! So the dust shell expands away from the star, then 193 or so years later the stars get close together and blow out another shell, lather, rinse, repeat.

In the JWST image of Apep we can see four such cycles! The most recent is the smallest (it’s had the least time to expand) and is shown in yellow. The next two are each larger, and the fourth is only partially seen, since its full extent is larger than the field of view in this image.

Part of the odd shape is due to the third star. It too emits a wind, which on human scales is huge, but still a pale whisper compared to its two companions. Still, it carves a hole in the shells, creating the wiggly pattern from about 10 o’clock to 2 o’clock in the image. The astronomers who worked on this data conclude this indicates the third star is a physical companion to the binary in the Apep system (and not just one randomly nearby), which can help them understand it better.

This animation, created using the image data, shows this all more clearly:

You can see the structure in the shells, and the huge hole in each shell (which, overall, makes a cone shape) as the animation rotates.

The scale of this is just immense. The winds blow out at speeds of 2,000 and 3,500 kilometers per second — about 1% the speed of light! — and remove as much as three times the mass of the Earth from each star every year. A whole planet’s worth of material, gone, three times over, every year! Amazing. The largest shell is roughly half a dozen light-years across. Huge.

The fate of these stars is not in question. Each will explode as a supernova, lighting up the galaxy and creating chaos in the Apep system. We’re roughly 6,000 – 14,000 light-years from it, so it’s likely no danger. On the other hand, one of them might explode as a gamma-ray burst, creating what is essentially a pair of narrow death rays that march across space and torch everything in their paths. It’s still too far away to do much damage to us, though to be honest I’d rather not test that assumption. Happily, it won’t happen for a while yet, a million years or more most likely, so it’s not something we need to worry about any time soon (and the narrow beam might miss us anyway).

Yeah, phew. Wolf-Rayet stars are scary enough without having one arcwelding our planet. But they’re also important to study. They make a lot of dust, which has profound effects on star formation, and tell us a lot about how massive stars behave at the violent ends of their lives. They also create a lot of the heavy elements that then seed other stars when they form, which literally makes up the iron in your blood and other ingredients of life that we need to exist at all. So these stars may be unsettling, but you wouldn’t be here without ones like them.

Ponder that while you look at that image.

Et alia

You can email me at [email protected] (though replies can take a while), and all my social media outlets are gathered together at about.me. Also, if you don’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter! And feel free to tell a friend or nine, too. Thanks!

Reply