- Bad Astronomy Newsletter

- Posts

- AMAZING image: Comet Lemmon encounters a meteor, kinda.

AMAZING image: Comet Lemmon encounters a meteor, kinda.

Also, a spinny new target for the asteroid-hunting mission Hayabusa2

The Trifid Nebula and environs. Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

October 27, 2025 Issue #949

Comet Lemmon and a persistent meteor

The bright comet gets photobombed by a bit of meteoric debris

I haven’t been able to see the new comet C/2025 A6 Lemmon yet, mostly due to trees (my view of the sky is limited since I live in a forest). But it’s bright enough right now to see naked eye from a dark site, or by binoculars if you have some light pollution. Of course it’s cloudy where I am right now, but if it clears up I may hop in the car and get to a wider-open spot to take a look.

Astronomer Gianluca Masi has had better luck. He was observing the comet with a telescope in Manciano, Italy on October 24th , and while he was taken images of a bright meteor flashed right across the field of view!

Even better, it left behind a trail (astronomers call it a train for some reason) of vaporized rock that glowed for a brief time… and also excited the atoms of oxygen high in the atmosphere, creating what’s called a persistent train, which can glow red for several minutes after the meteor. As winds blow, the train can get ripples in it, creating a lovely effect. And, as it happens, this meteor aligned so well with the comet that it made for an incredible image:

Comet C/2025 A6 Lemmon with a meteor’s persistent train. The fan of light below it is from clouds, and the fuzzy dots are stars that have been suppressed in post-processing to highlight the comet. Credit: Gianluca Masi

That’s epic! Mind you, the meteor was a few hundred kilometers away, while the comet was nearly a hundred million kilometers distant. So the red meteor train looking like it’s wrapped around the comet’s tail is an illusion borne of perspective.

The comet’s tail is blue likely due to carbon monoxide gas, which is frozen in the solid nucleus of the comet until warmed by the Sun. As the gas is ionized by sunlight, it glows blue. That’s common in comets.

And it’s so lovely. Let this inspire you, like it has with me, to go take a look.

Hayabusa2’s next target is smaller and spinnier than first thought

Asteroid 1998 KY26 makes for a difficult rendezvous

Determining the size of an asteroid is difficult. Only the very biggest are resolvable in Earthbound telescopes; that is, appearing as more than just a dot in images. For the most part we estimate their sizes making some decent but basic assumptions. For example, getting the distance to one is easy; it falls out of the orbit calculation. Then we can get its size by measuring its brightness — a bigger asteroid will be brighter. But the assumption in that case is how reflective it is. One that’s shiny (it has a high albedo) can be smaller and still look brighter than a bigger, darker one. That means we’re still estimating the size.

The asteroid 1998 KY26 is a small rock that can pass pretty close to Earth, making it a ripe target for spacecraft. In fact, the Japanese mission Hayabusa2, which visited the asteroid Ryugu and returned samples to Earth, is slated to rendezvous with it in July 2031. Before it gets there, though, we’d like to know as much about the asteroid as possible.

The asteroid passed Earth in 1998, and was close enough to ping it with radar. This is massively useful, since it can measures lots of properties of an asteroid like its size, spin rate, and even see surface features and whether it has a moon or not. At the time, the scientists concluded 1998 KY26 rotated once every 10.7 minutes, which was the fastest spinning asteroid known at the time. This spin rate is needed to get the size when radar is used, and they found the rock was about 30 meters in diameter (plus/minus 10 meters).

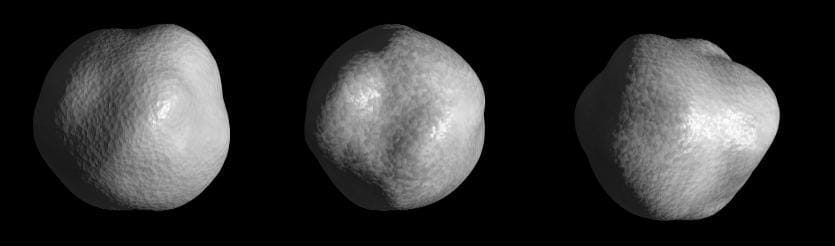

These models of 1998 KY26’s shape were calculated from the radar observations. It looks to be a lumpy sphere, and we’ll know for sure in 2031 when Hayabusa2 takes a peek. Credit: NASA's JPL Digital Image Animation Laboratory / Steve Ostro

However, astronomers observed it again in 2000, 2020, and 2024 using various telescopes [link to journal paper]. Looking at how its brightness changed over time, they conclude that the asteroid is spinning much faster than previously thought; rotating once every 5.35 minutes. Putting that back into the equations to get its size, they find it’s actually about 11 - 14 meters across, half what was found earlier.

Hayabusa2 is not planning on actually landing on the asteroid — it’s not clear this would even be possible for such a fast rotator, unless it were near one of the poles — but this does change how it will study it. Some cameras may need to take longer exposures, for example, and it could blur as it spins over that time. Of course, this is something we could have learned once the spacecraft got there, but here’s the thing: not every asteroid can be visited. By comparing the ground-based observations by in situ “ground truth”, we can learn how well we can observe these rocks from afar, and how confident we can be with the results. That means we can then look at other asteroids and understand them better as well.

An interesting thing about KY26 is that it’s the smallest asteroid that will ever have been visited. Decamater-sized asteroids (ones with diameters in the tens of meters range) are mostly a mystery, since they’re so small they are too faint to be seen easily (though JWST spotted quite a few in the main asteroid belt recently). It might prove to be a rubble pile — literally a pile of rocks. In kilometer-sized asteroids like Ryugu the force holding them together is mostly gravity. But in smaller ones like KY26 it might be the van der Waals force, which is vaguely similar to static electricity. Or, KY26 might be a monolithic rock. That would be exciting, since we’ve never seen one like that up close that’s so small. We could learn a lot from this.

Also, I just love it when we get to see asteroids in detail. They’re all interesting and weird, so there’s plenty of reason to study them. Hayabusa2 will pass by the stony asteroid (98943) Toifune in July 2026, by the way, so we won’t have to wait too long to see another one up close.

Et alia

You can email me at [email protected] (though replies can take a while), and all my social media outlets are gathered together at about.me. Also, if you don’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter! And feel free to tell a friend or nine, too. Thanks!

Reply